Michel de Montaigne, the sixteenth century French essayist, contends that it is madness “to judge the true and the false from our own capacities”.

He uses the example of a miracle. Humans can never agree on what constitutes a miracle. What may seem a miracle to one is easily explained by another. What is possible today seemed miraculous twenty years ago.

There is a silly arrogance in continuing to disdain something and to condemn it as false just because it seems unlikely to us

As soon as you declare anything to be impossible, you are claiming to know the limits and bounds of nature. But your knowledge, as a group or individually, is changing all the time. What once was thought impossible is now taken for granted. If you had never seen an ocean before, you would call a lake an ocean. Why judge of anything when you don’t have all the facts?

World map 1450, by Fra Mauro

Montaigne had a near death experience that showed him that not only do you not have all the facts, but you also cannot trust the evidence of your senses at all. The way that an event is seen by an outward observer may be quite different from the way it is experienced by the one undergoing it.

In a riding accident, he suffered the full weight of a very large man landing on him like a thunderbolt, knocking him unconscious, off his horse, “dead, stretched on my back, my face all bruised and skinned, my sword, which I had had in my hand, more than ten paces away, my belt in pieces, having no more motion or feeling than a log.”

Details courtesy Sarah Bakewell’s How to Live, or A Life of Montaigne.

He was picked up by his frightened servants and carried home, coughing, vomiting up clotted blood, thrashing about and ripping violently at his stomach. “My stomach was oppressed by the clotted blood; my hands flew to it of their own accord, as they often do where we itch, against the intention of our will.”

It looked to all observers as though he were experiencing a painful, violent death.

“It seemed to me that my life was hanging only by the tip of my lips; I closed my eyes in order, it seemed to me, to help push it out, and took pleasure in growing languid and letting myself go. It was an idea that was only floating on the surface of my soul, as delicate and feeble as all the rest, but in truth not only free from distress but mingled with that sweet feeling that people have who let themselves slide into sleep.”

Except he didn’t die. After several hours he recovered, lived another twenty years, lost all the fear of death which had plagued him as a young man, and wrote most of the Essais.

For weeks afterward Montaigne questioned the servants about what they had seen, intrigued by how contrary their observations were to his own experience, which was all of a peaceful, merciful release. Lying on his bed after the accident, he was anticipating “a happy death”.

Long afterward he wrote,”If you don’t know how to die, don’t worry; Nature will tell you what to do on the spot, fully and adequately. She will do this job perfectly for you; don’t bother your head about it.”

Nature does this perfectly

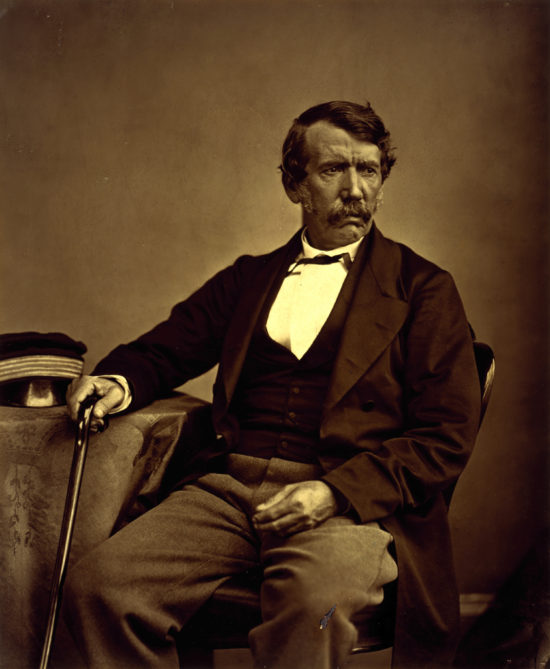

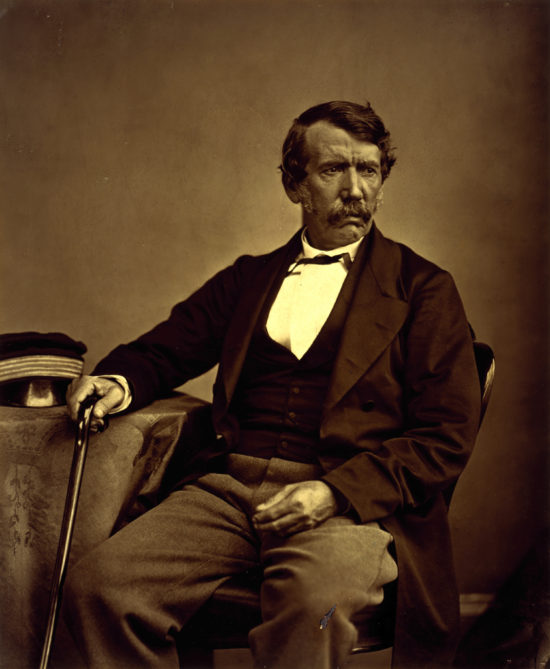

Another brush with the benevolent hand of nature was recorded by Dr. David Livingstone, the missionary and African explorer of the nineteenth century. Livingstone suffered a lion attack in an African village, trying to defend the village’s sheep. He shot the animal twice, which didn’t kill but enraged it. The lion “caught me by the shoulder as he sprang, and we both came to the ground together. Growling horribly close to my ear, (the lion) shook me as a terrier dog does a rat.” (The Life and African Explorations of David Livingstone).

We are reminded of Montaigne’s injunction against taking things as they seem. We don’t even know what we don’t know. Our knowledge is always limited and always changing. If you compare yourself now to yourself ten, twenty years ago, you will see this is true. What may look like a violent shock may well be felt as a floating euphoria.

In this case, what happened? A man was taken by a lion, was aware of injuries, a situation which we can imagine in one way only : as horrific.

Neither pain nor terror

Livingstone goes on. “The shock…caused a dreaminess, in which there was no sense of pain nor feeling of terror, though quite conscious of all that was happening.”

He was saved by the intervention of his servant, while the lion succumbed to the two bullets inside him. Livingstone treated his own wounds without anesthesia, and lived another twenty-one years.

How would the world have been different if Montaigne and Livingstone had died of their injuries? If they had not written of their travels, Livingstone, into the heart of Africa, and Montaigne, into the heart of himself.

Montaigne, on sadness:

I am among those who are most free from this emotion; neither like it nor think well of it, even though the world, by common consent, has decided to honor it with special favor. Wisdom is decked out in it; so are Virtue and Conscience – a daft and monstrous adornment

Wisdom is the knowledge that helps us to live. Montaigne’s whole life and Essais was a search for that knowledge.

To be alive is to be subject to constant change.

It does not help us to live if we imagine there is wisdom in sadness.

Why give so much power to sadness? Montaigne, who faced down his own end, knew, for the rest of his life, that all sadness and all fears were unreal, meaningless, and forever disabled.

And it is given us to look past death, and see the life beyond

A Course in Miracles, Workbook, Lesson 163